3 Sly Guys & Their Alamo Lies: “Forget the Alamo” Debunked

Forget the Alamo was not written for smart people, and by the time you finish reading this debunking, you will find that the authors are their own audience.

It is a book written for attention. It was written to please their political, academic and media comrades, but not smart people. Honest, reasonable, knowledgeable people won’t like Forget the Alamo and will be disgusted by the authors’ dishonesty and incompetence.

The premise of the first third of the book is that the Texas Revolution was about slavery. To be more precise, the authors make the claim that Texians revolted because the new centralist Mexican government was going to take their slaves.

Slavery The Cause of the Texas Revolution

That’s a bold assertion for a couple of journalists and a political consultant to make, especially given that no historian of any note has ever made it.

Here is their thesis straight from page 3 of the book.

There you have it: Texas revolted because the Mexican government was coming for the slaves.

In an honest work, such a claim would be followed by evidence to support it. But when tricksters have no evidence for their claim, they bury that fact in dense prose, and what follows page 3 is a sixty-seven page burial. Which creates a problem. How do you refute their evidence, when they offer no evidence?

All we can do is tell you what those sixty-seven pages actually contain.

Pages 4-5: Description of the cotton economy.

Pages 6-8: A synopsis of the history of Spanish Texas.

Pages 9-10: The Gutierrez-Magee expedition, the Battle of Medina.

Pages 11-14: Laffite in Texas, Indian troubles on the North Mexican frontier, the Long Expedition.

Pages 15-19: Moses Austin, Baron de Bastrop, Joaquin de Arredando, Stephen F. Austin.

Pages 20-22: How the Mexicans disliked slavery but Austin got them to allow it. (Pre Constitution of 1824)

Pages 23-28: The early days of Austin’s colony, the slavery debate in the Coahuila legislature and colonists’ response, the Freedonian Rebellion.

Pages 29-30: The indentured servant legislation.

Pages 31-32: The Guerrero Decree and the exemption of Texas.

Pages 32-33: The chaos of Mexican politics, Mier y Teran’s concern over the growing Anglo population, the law banning further American emigration, the necessity of slaves to the Texas economy.

Pages 34-40: The cotton market boom of 1831, Alaman closes the border, the Anahuac Disturbances, newcomers to Texas, Juan Davis Bradburn, William Barret Travis, the clash over runaway slaves from Louisiana, Santa Anna the Federalist.

Pages 41-42: Federalism, the attempt to make Texas a separate Mexican state, the Convention of 1832, the Convention of 1833, Austin goes to Mexico City.

Pages 43-44: Santa Anna, Gomez Farias.

Pages 45-48: Austin’s arrest, Austin urges calm from prison, Santa Anna makes concessions, Juan Almonte and his inspection tour of 1834.

48-49: Calm at the beginning of 1835, record cotton harvest, Santa Anna switches from Federalist to Centralist.

50-54: The sacking of Zacatecas, Cos sent to establish order in Texas after switch to centralism, Tejanos start the revolt, Coahuila asks for help against centralists and Juan Seguin goes to their aid, Anglos join the revolt, Bowie arrested while helping Seguin, Bowie’s escape, Bowie’s land dealings in Coahuila, Austin returns to Texas.

Page 55: The leadership vacuum without Austin, the War Dogs.

Pages 56-58: Travis’ background.

Pages 58-61: Travis’ actions in 1835.

Pages 61-62: Seguin, Navarro and other Tejanos confer, Austin supports the Constitution of 1824, Cos lands at Copano and heads to San Antonio, the Battle of Gonzales, “Come and Take It”, Seguin joins the Texians.

Page 63: Austin leads the army, offers to negotiate peace with Cos, Cos declines, Texians bicker, Sam Houston arrives on the scene.

Page 64: Sam Houston’s background.

Pages 65-66: The Texian military structure.

Pages 66-69: The Battle of Concepcion, prelude to the Siege of Bexar, formation of the provisional state government, Houston made commander of the regular army, the government calls for volunteers from the United States, Austin sent to raise money.

And that brings us to page 70, which begins, “Okay, so now the revolt is under way…” A revolt they told us way back on page 3 was over slavery. The authors then tell us Santa Anna was not such a bad guy and that the Mexicans were ardently abolitionist.

Were they?

The truth of the matter, which the authors would have discovered if they had done their research, is that slavery was not illegal in Mexico at the time of the Texas Revolution.

Here’s what really happened:

In 1829 an attempt to ban slavery failed in the Mexican Congress. President Guerrero was granted sweeping powers to thwart Spain’s attempt to retake the country. Jose Maria Tornel, the equivalent of the U.S. Speaker of the House, persuaded President Guerrero to use those emergency powers to abolish slavery in Mexico. (A little over two months later the president would exempt Texas.)

Then in 1831, eighteen months after Guerrero issued his decree banning slavery, it was annulled by the National Congress, along with most of the late president’s (they executed him) emergency decrees. Slavery was legal in Mexico at the time of the Texas Revolution. It remained legal until 1837, when the National Congress passed an emancipation law nearly a year after Texas had won independence.

Back to the book. On page 71 they finally offer something resembling evidence that Mexico was was on the verge of freeing the slaves in Texas: The Cos Decree of July 5, 1835.

The Cos Decree

We doubt the authors of Forget the Alamo have actually read the Cos Decree, as their writing about it is just a paraphrase from goofball Phillip Thomas Tucker’s Exodus From the Alamo (page 40). They even parrot his quote from the Matagorda Commission of Safety used in the same paragraph, changing it just slightly.

Had they read it in full, they might not have made the same mistake as Tucker, thinking it meant Mexico was coming for the slaves.

Here’s the whole thing:

As you can see, it’s telling everyone in Texas to forget their idea that governments should be elected and to get behind the centralist regime or face the consequences of war. It says, “Y’all have it good up there away from all the strife in the other states. Don’t mess it up. If you let those bad apples agitate you, I will make you regret it.”

The message of the broadside is simple: if you want to keep your “property” don’t rock the boat.

Property

Let’s take a closer look at that word - property - since the authors fixate on it and lend it a far narrower meaning than it had in the 19th century. If you recall, on page 3 of Forget the Alamo, the authors tell us that it was a code word for slavery used in pamphlets and newspapers. Here’s the quote:

“What did they fear losing? In the pamphlets and newspapers that swirled around the revolt, it was always called ‘property.’ ” -Forget the Alamo, p. 3

The only revolutionary “pamphlet” we’re aware of that mentions property is the Cos decree shown above. This may be a shortcoming on our part. If you know of any, we’d be thankful if you share them with us.

Now, newspapers we do know something about.

The University of North Texas hosts the Texas Digital Newspaper Program, which has digitized the newspaper holdings of every major repository in Texas. These historic newspapers are searchable online via The Portal to Texas History. It’s a treasure trove.

A search reveals the word “property” was used in thirty-six issues of Texas newspapers from January 1, 1835 through April 21, 1836, the date of the Battle of San Jacinto.

In only one instance can the use of the word “property” be reasonably construed to refer to slaves, and not other forms of property. That is in the January 23, 1836 edition of the Telegraph and Texas Register. The passage refers to President Guerrero’s 1829 decree outlawing slavery, and how he exempted Texas. (Here is the timeline of the laws regarding slavery in Mexican Texas).

Hardly a swirl of newspapers and pamphlets, but the Forget authors are emotionally tethered to the word “property,” as though they were the first to discover that the property of some 19th century estates included slaves. This was not news to those of us who have read a book or two, but as I said, smart people are not their target audience.

Inventing Greasers

One thing you quickly learn about the Forget the Alamo boys is they love to smear the dead, and if that means bearing false witness, so be it. A particularly disgusting example is found on page 79.

In describing events after the siege of Bexar and General Cos’ departure in December of 1835, the authors say the following:

“Those who stayed in San Antonio were mostly American adventurers, who promptly set to chasing senoritas and insulting the Tejanos, whom they termed ‘greasers.’ ” -Forget the Alamo, p. 79

And it’s a lie. The etymology of “greaser” is well established. The first documented use of the term is in an 1842 letter from an anonymous Santa Fe Expedition prisoner being held in Matamoros.

The letter was printed in the April 20, 1842 issue of the Houston Telegraph and Texas Register. Who the word was used by and who it was used to refer to is interesting.

The letter writer was describing Santa Anna’s method of recruiting soldados for a reconquest of Texas:

The first usage of “greaser” as a racial epithet does not appear until the beginning of the Mexican war in 1846. That’s over a decade after the Forget Boys have Texians running around Bexar using it. Writers of low-grade historical fiction are more diligent in their research.

The authors have done one of three things here:

They assumed that Anglos in 1835 were using the word because Anglo = racist,

They are quoting a writer as ignorant as themselves, or

They made it up to fit neatly into their story.

If it’s any of the above, it calls into question everything they have written in the past and may write in the future. Editors: you accept their work at the peril of your own reputation.

Side Note: Where does the word “greaser” come from?

Gustavo Arellano in the September 12, 2016 edition of his syndicated “Ask a Mexican” column, as seen in Monterey Now speculates as follows:

“So where did greaser come from? The Mexican’s theory: It’s an English speaker’s mispronunciation of grosero, which technically means “rude” but sounds like “gross”—a false cognate if ever there was one. We at least know that the earliest use of the term referred to clothing, so perhaps gabachos picked it up from Mexican elites ridiculing poor Mexis. Silly folk etymology, Gabacho Academic? Perhaps. But still better than yours.”

Racism! Racism! Racism!

The word “racist” is used twenty-five times in Forget the Alamo. The word “racism” appears seventeen times. We are told that many newcomers to Texas were “racist southerners.” That Governor Henry Smith “was a thoroughgoing racist.” That United States Minister to Mexico Joel Poinsett “was a deep-seated racist who viewed Mexican politicians as bickering children.”

This is presentism at its worst, or finest, depending how you look at it. Racism/Racist are modern concepts and the Forget Crew demonstrate a cloying need to impose today’s attitudes on yesterday’s men.

The concept of racism, as we understand it today, did not exist at the time of the Texas Revolution. In fact, the word “racism” did not appear until the late 1920s when it was used by self-described fascist political philosophers to refer to ethnic loyalty, which they believed was destructive to society. The term “racist” didn’t come along till the brink of World War II, when it was used to describe animosity toward other ethnicities.

This will come as a shock to some, but people in the early 19th century didn’t think like we do today. If you learn nothing else from history, learn this: human beings are tribal, and every tribe thinks itself the best tribe to belong to.

This tribal instinct today attaches itself to political parties, schools, sports teams, you name it. In the nineteenth century your tribal loyalty was to your church, your state, your region, your country, and yes, your ethnicity – though not necessarily in that order.

Your views of other “tribes” were shaded by a chauvinism for your own, to a greater or lesser degree. This was the norm not just for white Americans, but for Mexicans, Native Americans, Japanese, everybody everywhere. Get the picture? Even the slaves of wealthy whites thought themselves the social superiors of poor whites.

To illustrate this simple concept, let’s look at the writings of poor Joel Poinsett whom the authors of Forget the Alamo have smeared as a racist (he was a lifelong friend of Lorenzo de Zavala by the way) and Juan Almonte.

This passage is from Poinsett’s Notes on Mexico, written during his travels through the newly independent country in 1822.

Now compare it to the description of Anglo colonists written by Colonel Juan Almonte during his 1834 inspection of Texas.

Do you get it now?

Sparks & Booty

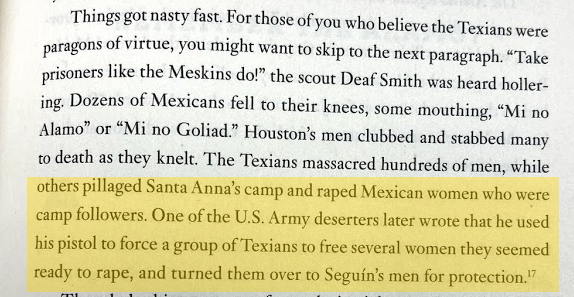

We examined this passage from page 141 in our original fact check article, but it bears looking at again.

This time we’ll start with the claim that Texian soldiers pillaged Santa Anna’s camp. They didn’t.

As soon as the the Texian officers knew the day was theirs, a guard was set on the Mexican camp to prevent pillaging. $12,000 in gold and silver was captured. The men voted to give $3000 to the Texas Navy. The rest was divided between them ($11.50 per man) to be spent at the booty auction (yes, that’s what they called it) on April 26 where the arms and goods captured in Santa Anna’s camp were sold.

Rape and pillage are like chocolate and peanut butter to trite writers. If you see one, you know the other is coming.

The footnote for the claim that Texian soldiers raped Mexican woman at the Battle of San Jacinto is sourced to Bill and Marjorie Walraven’s Southwestern Historical Quarterly article from 2004 titled, “The Sabine Chute: The U.S. Army and the Texas Revolution.”

Here’s what that article says:

Former Land Commissioner Jerry Patterson pressed the writers to answer for this deception. One of the authors, business journalist Chris Tomlinson, responded via email:

“I stand by my interpretation that a soldier using a bayonet to menace a woman on a 19th-century battlefield suggests a sexual assault. Sparks would have never said it, but rape was common in such situations, and the suggestion that the Texian troops were somehow above it is absurd. Rape was epidemic in the 19th century, particularly against women of color.” -Chris Tomlinson

Oh Chris, if you see the word “bayonet” and immediately think of the male organ, the internet has ruined you.

First, people in the nineteenth century were quite capable of writing about rape and did so. It was a frequent occurrence in raids by plains tribes and was usually referred to as “outrage” or “defilement.”

If the authors of Forget the Alamo were seekers of truth they would have gone straight to Sparks’ account and read it in context. That would have saved them much embarrassment. It was always just a few keystrokes away. Here you go.

No End

That’s not the end of what’s wrong with Forget the Alamo. This debunking could go on and on and on. The book is a target rich environment.

We could tell you about how they get the casualty numbers for San Jacinto wrong, how they flub Zavala’s role with the Permanent Council, how they say the Tejanos under Juan Seguin fought as cavalry at San Jacinto (they fought as infantry,) etc., etc., etc.

Lots of small, sloppy errors that hint at poor research and a lack of command of the subject matter.

We could tell you how the authors claim the Texians used code words like “hands” and “negroes” to avoid using the word “slave,” even though those were the most commonly used terms wherever slavery existed – North and South.

Lots of bold, ridiculous claims that reek of modern men who lack a basic understanding of 19th century vernacular and culture.

Credit Where It’s Due

In case anyone should think we’re not being objective and just want to trash the book, we’d would like to say that the section on Travis’ line in the sand is an excellent telling of everything we know about the origin of that story.

This makes the rest of the book all the more sad and pathetic. The juvenile cover is revelatory of what’s inside. The authors were capable of writing a fair and entertaining popular history of the Alamo, but being possessed by an ideology, they have instead vandalized history.